Foreword

Technology is the engine that powers superpowers. As the chair of the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI), I led the effort that ultimately delivered a harsh message to the U.S. Congress and to the administration: America is not prepared to defend or compete in the AI era. The fact is that America has been technologically dominant for so long that some U.S. leaders came to take it for granted. They were wrong. A second technological superpower, China, has emerged. It happened with such astonishing speed that we’re all still straining to understand the implications.

Washington has awakened to find the United States deeply technologically enmeshed with its chief long-term rival. America built those technology ties over many years and for lots of good reasons. China’s tech sector continues to benefit American businesses, universities, and citizens in myriad ways—providing critical skilled labor and revenue to sustain U.S. R&D, for example. But that same Chinese tech sector also powers Beijing’s military build-up, unfair trade practices, and repressive social control.

What should we do about this? In Washington, many people I talk to give a similar answer. They say that some degree of technological separation from China is necessary, but we shouldn’t go so far as to harm U.S. interests in the process. That’s exactly right, of course, but it’s also pretty vague. How partial should this partial separation be—would 15 percent of U.S.-China technological ties be severed, or 85 percent? Which technologies would fall on either side of the cut line? And what, really, is the strategy for America’s long-term technology relationship with China? The further I probe, the less clarity and consensus I find.

In fairness, these are serious dilemmas. They’re also unfamiliar. “Decoupling” entered the Washington lexicon just a few years ago, and it represents a dramatic break from earlier assumptions. In 2018, for example, I remarked that the global internet would probably bifurcate into a Chinese-led internet and a U.S.-led internet. Back then, this idea was still novel enough that the comment made headlines around the world. Now, the prediction has already come halfway true. Meanwhile, policymakers—who usually aren’t technologists—have scrambled to educate themselves about the intricate global supply chains that still link the United States, China, and many other countries.

In 2019, I was appointed to be the chair of the NSCAI, a congressionally mandated bipartisan commission that was charged with “consider[ing] the methods and means necessary to advance the development of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and associated technologies to comprehensively address the national security and defense needs of the United States.”1 I worked with leaders in industry, academia, and government to formulate recommendations that would be adopted by Congress, the administration, and departments and agencies.

We were successful, but this effort did not go far enough. That is why I continue to advocate for major legislation (such as the United States Innovation and Competition Act and the America COMPETES Act), to develop the next phase of implementable policy options (through the recently launched Special Competitive Studies Project), to support bold and ambitious research on the hardest AI problems (via my new AI2050 initiative), and to elevate public discussion (in my latest book, The Age of AI, with Henry Kissinger and Daniel Huttenlocher).

Still, there is so much more work to do to secure America’s technological future in the context of a rising China. Given the high stakes and dizzying complexity of the challenges, many U.S. leaders are still searching for a mental framework—a set of analytical tools to help them answer the most fundamental questions of strategy and policy. The China Strategy Group, a bipartisan group of thinkers and doers I convened with Jared Cohen in 2020, sought to develop those kinds of frameworks. One of our key findings was that such profound national dilemmas call for deeper analysis by a broader range of independent voices.

That’s why I was so pleased to read Jon Bateman’s major new report, “U.S.-China Technological ‘Decoupling’: A Strategy and Policy Framework.” Jon is a brilliant thinker who has written an exceptional guidebook and blueprint for U.S. action. His report builds on recommendations outlined by the NSCAI and the China Strategy Group. It’s a major achievement, and I strongly hope that policymakers pay attention to it.

There is no shortage of analysis today on U.S.-China tech policy, but Jon’s report stands out for its ambition, clarity, and rigor. To start with, he avoids two of the biggest and most common pitfalls: offering hazy strategic ideas without explaining how to implement them, or cataloging a laundry list of policies without any discernible strategy. Instead, Jon draws a straight line from the heights of American grand strategy to the trenches of agency decisionmaking. With this methodical approach he outlines a smart, achievable agenda for a remarkable range of U.S. national security and economic goals. I particularly appreciated Jon’s prolific use of case studies to ground his proposals in technological reality.

Jon is not afraid to stake a position, and some of my favorite parts of his report were those that I disagreed with. He argues, for example, that the military importance of AI may be overestimated—or, at least, that the era of what China calls “intelligentized warfare” is probably still a long way away. I’ll take the other side of that bet, but I still found Jon’s analysis to be evenhanded and thought-provoking. And at this perilous moment in U.S. history, we simply can’t afford groupthink. With calls for a hard “decoupling” getting louder, fewer people are willing to say (or even ask) where it all ends. Jon is one of those people, and I applaud him for it.

The paradoxes of the U.S.-China tech relationship are not going away. The United States will need to continually reassess whether and how to remain interdependent with our major international rival. The decisions will be difficult, the debates heated. Jon’s report is among the best guides I have seen and will remain a touchstone for years to come.

Eric Schmidt

Co-founder, Schmidt Futures

Chair, Special Competitive Studies Project

Former CEO & Chairman, Google

Executive Summary

A partial “decoupling”2 of U.S. and Chinese technology ecosystems is well underway. Beijing plays an active role in this process, as do other governments and private actors around the world. But the U.S. government has been a primary driver in recent years with its increased use of technology restrictions: export controls, divestment orders, licensing denials, visa bans, sanctions, tariffs, and the like. There is bipartisan support for at least some bolstering of U.S. tech controls, particularly for so-called strategic technologies, where Chinese advancement or influence could most threaten America’s national security and economic interests. But what exactly are these strategic technologies, and how hard should the U.S. government push to control them? Where is the responsible stopping point—the line beyond which technology restrictions aimed at China do more harm than good to America?

The United States cannot afford simply to muddle through technological “decoupling,” one of the most consequential global trends of the early twenty-first century.

These are vexing questions with few, if any, clear answers. Yet the United States cannot afford simply to muddle through technological decoupling, one of the most consequential global trends of the early twenty-first century. The U.S. technology base—foundational to national well-being and power—is thoroughly enmeshed with China in a larger, globe-spanning technological web. Cutting many strands of this web to reweave them into new patterns will be daunting and dangerous. Without a clear strategy, the U.S. government risks doing too little or—more likely—too much to curb technological interdependence with China. In particular, Washington may accidentally set in motion a chaotic, runaway decoupling that it cannot predict or control.

Sharper thinking and more informed debates are needed to develop a coherent, durable strategy. Today, disparate U.S. objectives are frequently lumped together into amorphous constructs like “technology competition.” Familiar terms like “supply chain security” often fail to clarify such basic matters as which U.S. interests must be secured and why. Important decisions are siloed within opaque forums (like the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States [CFIUS]), narrow specialties (like export control law), or individual industries (like semiconductors), concealing the bigger picture. The traditional concerns of “tech policy” and “China policy” receive outsized attention, while second-order implications in other areas (such as climate policy) get short shrift. And as China discourse in the United States becomes more politically charged, arguments for preserving technology ties are increasingly muted or not voiced at all.

This report aims to address these gaps and show how American leaders can navigate the vast, perilous, largely unmapped terrain of technological decoupling. First, it gives an overview of U.S. thinking and policy—describing how U.S. views on Chinese technology have evolved in recent years and explaining the many tools that Washington uses to curb U.S.-China technological interdependence. Second, it frames the major strategic choices facing U.S. leaders—summarizing three proposed strategies for technological decoupling and advocating a middle path that preserves and expands America’s options. Third, it translates this strategy into implementable policies and processes—proposing specific objectives for U.S. federal agencies and identifying the technology areas where government controls are (or are not) warranted. The report also highlights many domestic investments and other self-improvement measures that must go hand in hand with restrictive action.

The Evolution of U.S. Thinking and Policy

The U.S. government’s interest in technological decoupling has risen dramatically since the mid-2010s. During this period, Beijing’s growing strength and more troubling behavior at home and abroad led U.S. leaders to revise their views of China, deeming it America’s primary state threat. At the same time, techno-nationalist ideas—depicting technology as an arena for interstate struggle rather than a neutral global marketplace—became ascendant around the world and eventually prevailed in Washington. Together, these two trends produced a new American techno-nationalism focused principally on China. It first took shape during former president Barack Obama’s second term, was elevated and implemented under former president Donald Trump, and has been largely embraced by President Joe Biden.

Early U.S. actions were mainly “defensive”: restrictive measures aimed at thwarting or containing Chinese technology threats. Export and import controls, inbound and outbound investment restrictions, telecommunications and electronics licensing regimes, visa bans, financial sanctions, technology transaction rules, federal spending limits, and law enforcement actions have more frequently and intensively targeted China. Lately, Washington has increased its focus on “offensive” measures—positive actions to nurture America’s own technological strength, such as investments in research and development (R&D) and education. Yet despite this offensive pivot, defensive measures continue to multiply and raise some of the most acute policy dilemmas. For example, cracking down on illicit Chinese technology transfer at U.S. universities can chill valuable scientific collaboration, and banning Chinese technologies on national security grounds may prompt Beijing (or others) to broaden their own trade barriers.

U.S. policymakers must have a firm grasp of the many different tools used to curb bilateral technology interdependence. Defensive tools are often described generically as “sanctions” or “blacklists,” but this conflates distinct legal authorities with a range of effects and implementing agencies. For example, SenseTime and Hytera are among the Chinese tech firms most targeted by U.S. controls, yet the restrictions imposed on each company do not overlap at all. Huawei, meanwhile, suffers from nearly all of the controls placed on both SenseTime and Hytera, plus others that are completely unique. To clarify the picture, this report offers a primer on key U.S. defensive authorities and how they have targeted the Chinese tech sector.

Under U.S. law, officials have vast discretion to impose technological decoupling. They need only invoke pliable concepts like “national security” or “the public interest” to restrict how technology products, services, and inputs move between America and China. Most restrictive powers have been used to a small fraction of their full decoupling potential. At the same time, restrictive authorities are fragmented across multiple agencies and policy domains. This combination of great power and great complexity increases the risk that U.S. technology controls will be poorly conceived or work at cross-purposes. It is therefore essential to develop a government-wide strategy that can prevent overreach and align disparate elements into a coherent whole.

Choosing a Strategy

A U.S. strategy for decoupling should envision the kind of technology relationship that America hopes to have with China, provide a rationale for this vision, and explain how it can be made into reality. A sound strategy would start with a multidimensional assessment of U.S.-China tech ties and their wide-ranging effects on diverse American interests. In fact, a strategy for technological decoupling should consider more than just tech-specific or China-specific concerns. It should be rooted in a larger U.S. grand strategy that reconciles decoupling with other national priorities, from international trade to domestic political stability to global climate change, that might be impacted directly or indirectly. Washington still lacks such a decoupling strategy, even as it continually imposes new tech controls on China.

Leading proposals can be grouped into three general camps. First, a “restrictionist” camp believes that the U.S.-China technology relationship is zero-sum and that it tends to favor Beijing, necessitating dramatic curtailment of bilateral tech ties. This group—including China hawks, some human rights defenders, and many national security officials—fears U.S. complacency during what it sees as a closing window to prevent China’s technological dominance. Second, a “cooperationist” camp perceives U.S.-China tech ties as non-zero-sum and largely beneficial to America, casting doubt on key elements of Washington’s decoupling agenda. This group—including many business interests, techno-globalist activists, and some progressives—fears U.S. overreaction, inflated threat perceptions, and excessive confidence in restrictive tools.

Third, a “centrist” camp identifies the U.S.-China tech relationship as complex and uncertain, with both zero-sum and non-zero-sum elements and mixed costs and benefits for both countries. Centrists want focused, finely tuned defensive measures plus large offensive investments. This group—including many mainstream think tank analysts, moderate political figures, and some state and local leaders—fears U.S. incapacity to balance interdependence and decoupling. Key capacity challenges include securing public-private coordination, mapping complex supply chains, and overcoming Washington gridlock, polarization, and bureaucratic clumsiness.

The United States should adopt a centrist strategy. The very existence of a heated debate among these three camps is itself an argument for the careful incrementalism that centrists espouse. We are still in the early years of a radically new phase in U.S.-China relations and only on the cusp of far-reaching global transformations promised by artificial intelligence (AI) and other emerging technologies. These coming changes, although unquestionably significant, remain difficult for present-day observers to assess. Policymakers should play for more time—preserving and expanding American options while the future comes into sharper focus.

The primary effort should be “offensive”: new investments and incentives to bolster and diversify innovation pathways, supply chains, talent pipelines, and revenue models in strategic technology areas. The United States has far more influence over its own technological strength than it has over China’s, and such investments act as a hedge against multiple scenarios. They can prepare America for full-scope technological decoupling with fewer costs and risks, should that become necessary, or they can position U.S. firms to compete better in a still-globalized technology marketplace.

Because offensive investments are challenging to implement and take a long time to pay off, fast-acting “defensive” restrictions should be used to buy time. Washington should institute controls in technology areas where China seems close to securing unique, strategically significant, and long-lasting advantages. Defensive measures can help to forestall Chinese breakthroughs long enough for U.S. offensive efforts to bear fruit.

However, restrictive tools should be confined to a secondary, supporting role and only used in compelling circumstances. Technology restrictions can be costly (harming U.S. industries and innovators), imprecise (chilling more activity than intended), and even futile (failing to remedy the relevant Chinese tech threats). Restrictive tools by themselves cannot ensure U.S. technological preeminence over the long haul, but they can and should frustrate Chinese dominance in the short run, preserving competitive opportunities while America regroups and regains momentum in key technology areas.

Restrictive tools by themselves cannot ensure U.S. technological preeminence over the long haul, but they can and should frustrate Chinese dominance in the short run.

A centrist strategy of this kind will also help the U.S. government maintain its control over the decoupling process—keeping its pace and scope aligned with American needs. U.S. policymakers have enjoyed the luxury of control during recent years, as Washington took the initiative while Beijing, other governments, and private entities around the world were comparably cautious and reactive in technological decoupling. But as decoupling accelerates, these outside actors increasingly seek to seize initiative for themselves—for example, preempting future U.S. restrictions by acting first to reduce technology interdependence on their own terms. Meanwhile, decoupling has slowly begun to shift power within the United States toward political figures, commercial actors, and national security voices who advocate even stronger restrictive measures.

These dynamics create risks of unanticipated escalatory spirals. Washington might aim for a modest level of decoupling but end up with something broader, faster, and messier. In a worst-case scenario, the United States could accidentally set in motion a frenzied, ever-intensifying cycle of decoupling that races well ahead of what the nation can afford. A centrist strategy can minimize this risk by ensuring that technology restrictions are targeted and precise. The United States must then communicate this strategic intention, and share more details of specific policies, to help stabilize expectations in China and elsewhere. Such clarity cuts against the grain for U.S. leaders, who like to preserve their own discretion and struggle to make credible commitments across presidential administrations. But in a complex and interdependent global technology landscape, silence or ambiguity may actually cede control to others.

Translating Strategy Into Policy and Process

Any U.S. strategy—whether restrictionist, cooperationist, or centrist—must be translated into policies and processes to guide agency-level decisions. This is no simple task. It requires evaluating a host of technology areas, weighing numerous costs and benefits through the lens of multiple expert disciplines. Meaningful guidance must move past generalities and express clear policy choices, even in the face of uncertainty and a fraught domestic atmosphere. Thus, although many observers say that technological decoupling should be bounded and partial, there are few comprehensive, detailed proposals for how and where to draw such boundaries.

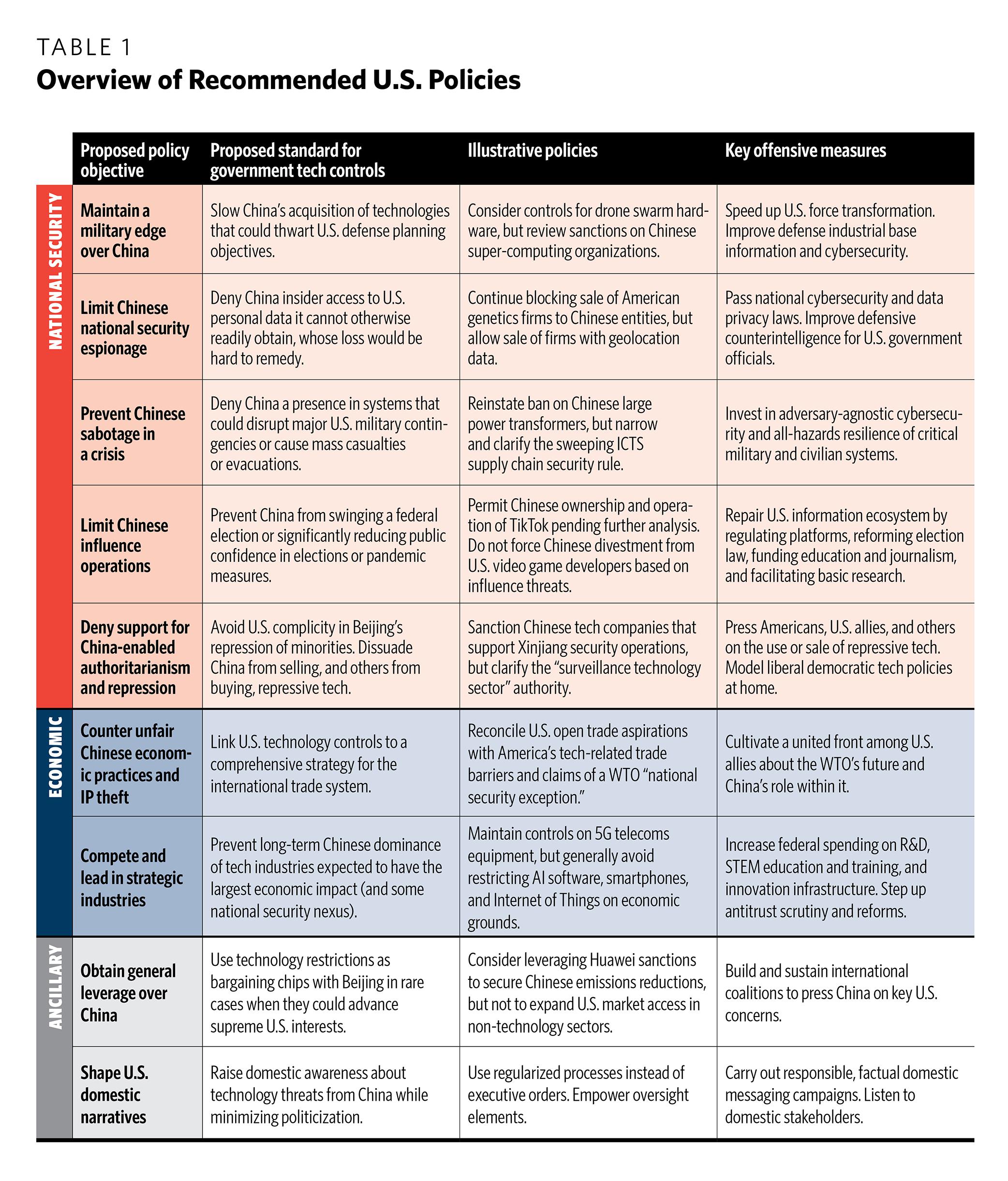

To develop such guidance, this report unpacks the many U.S. interests at stake and proposes nine policy objectives for technological decoupling. National security objectives include maintaining a military edge over China, limiting Chinese national security espionage, preventing Chinese sabotage in a crisis, limiting Chinese influence operations, and denying support for Chinese or China-enabled authoritarianism and repression. Economic objectives include countering unfair Chinese practices and intellectual property (IP) theft, and competing and leading in strategic industries. Then there are ancillary objectives—non-technology goals that also influence American decoupling policy: obtaining general leverage over China, and shaping U.S. domestic narratives. These nine objectives, although linked, raise many distinct issues and dilemmas. They cannot be treated as interchangeable responses to an undifferentiated mass of “Chinese tech threats”—an all-too-typical approach.

The next step, and the heart of this report, is a careful review of the role U.S. technology controls should play in achieving these policy objectives (see Table 1). Taking each objective in turn, the report weighs the risks and benefits of U.S.-China technological interdependence against the risks and benefits of U.S. government technology controls. This analysis leads to a series of proposed dividing lines—implementable standards for determining which technologies warrant restrictions and which do not. Specific examples help illustrate how these dividing lines would work in practice. Offensive measures essential to each objective are also highlighted. By considering the full gamut of U.S. interests across many different technology areas, the report shows what a centrist decoupling might look like and how agencies could implement it.

This step-by-step process demonstrates several points that bolster the case for a centrist approach. First, the most strategically significant technologies (like 5G telecommunications equipment and semiconductors) are few in number and already subject to strong U.S. government controls. A handful of other technology areas may need tighter China-oriented restrictions—for example, drone swarms, the U.S. bulk power system, and technologies sold to Xinjiang. Yet certain China-focused controls seem counterproductive in a number of other high-profile areas, such as geolocation data, social media platforms, and consumer devices like smartphones. Second, official U.S. policy goals remain dangerously vague and open-ended. To avoid costly and quixotic technology wars, Washington must publicly clarify its vision for the global tech trade and set more achievable ambitions for countering techno-authoritarianism, maintaining a military edge over China, and preventing Chinese espionage, sabotage, and influence operations. Third, offensive policies have the greatest long-term potential for strengthening U.S. technology leadership, competitiveness, and resilience—and thereby achieving security and prosperity. Although technology restrictions are the primary subject of this report, they cannot be the primary focus of policymakers.

Acknowledgements

The author is deeply grateful to George Perkovich for his patient guidance and penetrating reviews of this report throughout its development. Special thanks also go to Marjory Blumenthal, Tom Carothers, Mark Chandler, Chris Chivvis, Tino Cuéllar, Doug Farrar, Steve Feldstein, Sarah Gordon, Yukon Huang, Jim Miller, Mike Nelson, Matt Sheehan, Stephen Wertheim, and Tong Zhao for their valuable written feedback on drafts. Conversations with many others—in government, the private sector, academia, and civil society—helped to test and sharpen the report’s underlying ideas. Thanks are also owed to Evan Burke, Emeizmi Mandagi, Nikhil Manglik, and Arthur Nelson for research assistance, and to Isabella Furth, Natalie Brase, Jocelyn Soly, and Amy Mellon for editing and design. This report is the author’s sole responsibility and does not represent the views of any other person or institution.

The research for and writing of this report were supported by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Editorial production and dissemination were supported by a grant from Schmidt Futures

Abbreviations

AI: Artificial intelligence

CBP: Customs and Border Protection

CCL: Commerce Control List

CFIUS: Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States

DHS: Department of Homeland Security

DOD: Department of Defense

EAR: Export Administration Regulations

ECRA: Export Control Reform Act

FCC: Federal Communications Commission

FIRRMA: Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act

IC: Intelligence Community

ICTS: Information and communications technology or services

IEEPA: International Emergency Economic Powers Act

INA: Immigration and Nationality Act

ITAR: International Traffic in Arms Regulations

MEU: Military End-User

NSC: National Security Council

PLA: People’s Liberation Army

PRC: People’s Republic of China

R&D: Research and development

SDN: Specially Designated Nationals

SEC: Securities and Exchange Commission

STEM: Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

USITC: U.S. International Trade Commission

USML: U.S. Munitions List

USTR: U.S. Trade Representative

WTO: World Trade Organization

Notes

1 From the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence homepage at https://www.nscai.gov/.

2 “Technological decoupling” is a contested and sometimes politically charged phrase. In its strongest form, it can mean a total technological divorce between the United States and China—a very grave prospect currently favored only by a few radical voices. In its weaker form, it can refer more generally to the kind of marginal reduction of technological interdependence seen for the last several years. This report uses the latter meaning. Although “decoupling” can carry conflicting and at times misleading meanings, no other single term has yet managed to displace it in common usage.

This report is about the decoupling of “technology.” It does not focus on the range of other sectors (such as medical supplies, finance, entertainment, agriculture, and real estate) where U.S. analysts or officials have also proposed some partial decoupling from China. That said, “technology” is an elusive concept. While policymakers often speak of a distinct “tech sector” (which they sometimes equate with “Silicon Valley”), the truth is that every commercial sector employs, adapts, and develops technologies. Hence, loose talk of “technological decoupling” can often be confusing or misleading. Policymakers need more precise analysis of specific technology-related U.S. interests and objectives, as this report seeks to provide.

Within the broad category of technology, this report focuses mainly on digitally oriented technologies, whose major value stems from software, data, communications, and networks. Examples include machine learning systems, social media platforms, and large data caches. These raise particularly acute policy dilemmas, such as how to distinguish between dual-use applications and how to manage globalized supply chains and information flows. The report also addresses mixed digital-physical technologies, where hardware innovation is a crucial source of value; these include semiconductors, drones, and telecommunications equipment. However, highly physically oriented technologies—like nuclear reactors, advanced materials, and hypersonics—are not an explicit focus.

Finally, this report is concerned both with finished technology (end products and services) and with technology inputs. The latter includes elements of what is called “the supply chain,” such as technology components, raw materials, data, know-how, and human capital that flow between the United States and China. It also includes financial support. U.S. and Chinese actors have each made significant investments in the other country’s tech companies, and U.S. and Chinese tech companies receive significant revenue from sales to the other country’s home markets. These financial flows can be as important as the supply chain itself, or even more so, and have become a major policy battleground.